The exhibition publication includes articles by curator Mats Engström and art critic Thomas Millroth. On this page you can read the publication texts in English.

A DIFFERENT WORLD – ART FROM SANKT LARS HOSPITAL

Mats Engström, Curator Kulturen in Lund

Region Skåne’s medical history collections hold around 600 works of art referred to as ‘patient art’. These are artworks made by patients admitted to the the mental hospital Sankt Lars in Lund. The exhibition displays a selection of these objects. It is, in a way, correct to refer to these works as ‘patient art’, as they were created by patients in the hospital. At the same time, they demonstrate a desire to create and communicate – very universal needs shared by all people. Some of the creators, such as Carl Fredrik Hill and Ernst Ljungh, were professionally educated artists. What all of the artworks have in common is that they have left the world of traditional imagery behind.

Considering the fact that medical records from Sankt Lars portray very negative attitudes to these artworks, it is perhaps unexpected that the creations have been preserved at all. One explanation is that medical professionals started showing an interest in the art of ‘the insane’ in the 19th century. Within the expanding field of psychiatry, doctors wanted to investigate whether there was a connection between these creations and the illnesses the patients suffered from. Perhaps the artworks could be used to diagnose mental disorders?

At the same time, a new art form with new ideals was emerging. The odd, defiant and unique attracted much attention, which in turn revived old ideas of the connection between madness and genius. True art could only be created by people on the fringes of society, who were thought to have the power to connect with their inner emotions. This idea aligned well with the emerging field of psychoanalysis, in which the subconscious played a central role. Was it possible for the mentally ill to access areas of their subconscious selves without being hindered by the conventions of society?

A key figure in this context is Dr Hans Prinzhorn (1886-1933). He was one of the first to regard the creations of the patients as artistic rather than morbid. To Prinzhorn, the emphasis was on trying to understand the true core of creativity, not the disease. His book Bildnerei der Geisteskranken (‘Artistry of the mentally ill’) was published in 1922. It contained many images from the collection of patient art that Prinzhorn had accumulated from different psychiatric clinics over the years. The book would eventually inspire many contemporary art movements, such as Dadaism and Surrealism. The Surrealists, with André Breton leading the way, were especially enthusiastic, and regarded the irrational as well as the automatic as highly desirable.

In 1915, the Swedish psychiatrist Bror Gadelius (1862-1938) wrote that patient art illustrated ‘the primitive artistic tendencies and the basic sense of form, colour and rhythm, which, along with so many other things, can be found among the ruins of the human soul’. The creative, mentally ill patient suddenly blended in with the image of the Bohemian artistic soul – an eccentric person on the fringes of society, who had the ability to let their creativity flow freely, without restrictions.

One who was especially preoccupied with the idea of unrestricted creativity was the artist Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985). From 1945 onwards, he collected thousands of artworks from different mental institutions in Europe. He sought to promote the uneducated artists, those who never saw themselves as artists. Dubuffet believed that only people who were not limited by contemporary cultural structures could create art. The uneducated artists did not, according to Dubuffet, draw any inspiration from their surroundings at all, only from emotions coming from themselves. Dubuffet called it ‘l’art brut’, raw art.

Eventually, Dubuffet backtracked slightly from his radical views on genuine art (and genuine artists) – no human being could exist completely outside their own culture, regardless of their mental health status. Or, as the author Birgitta Trotzig so aptly phrases it: ‘one only needs to walk through an ordinary, dusty local history museum to realise that this separation between culture and nature, between art brut and art cultural, clearly does not exist there’.

ARTISTS´ BOOKS ON THE EDGE OF EXISTENCE

Thomas Millroth, art critic

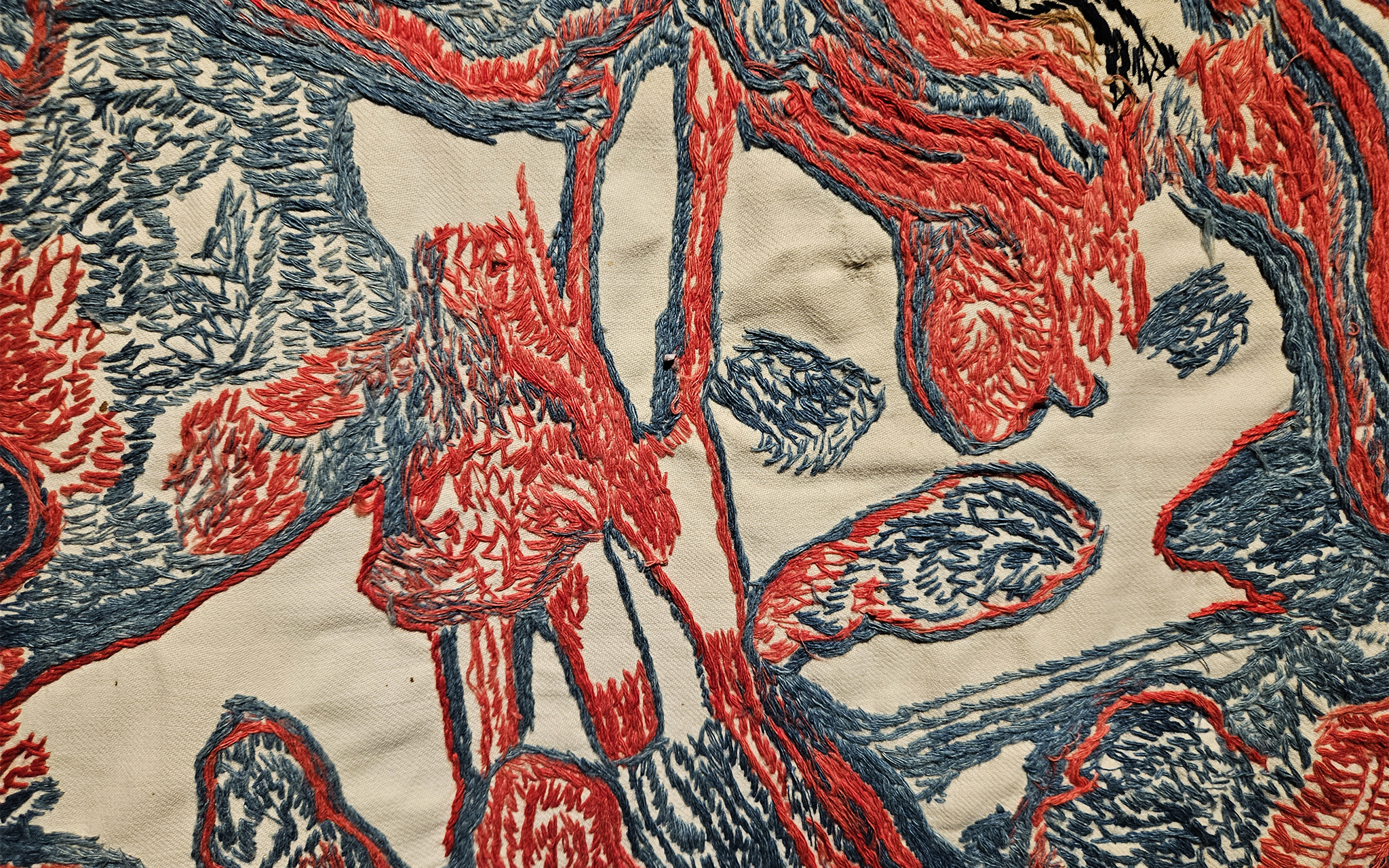

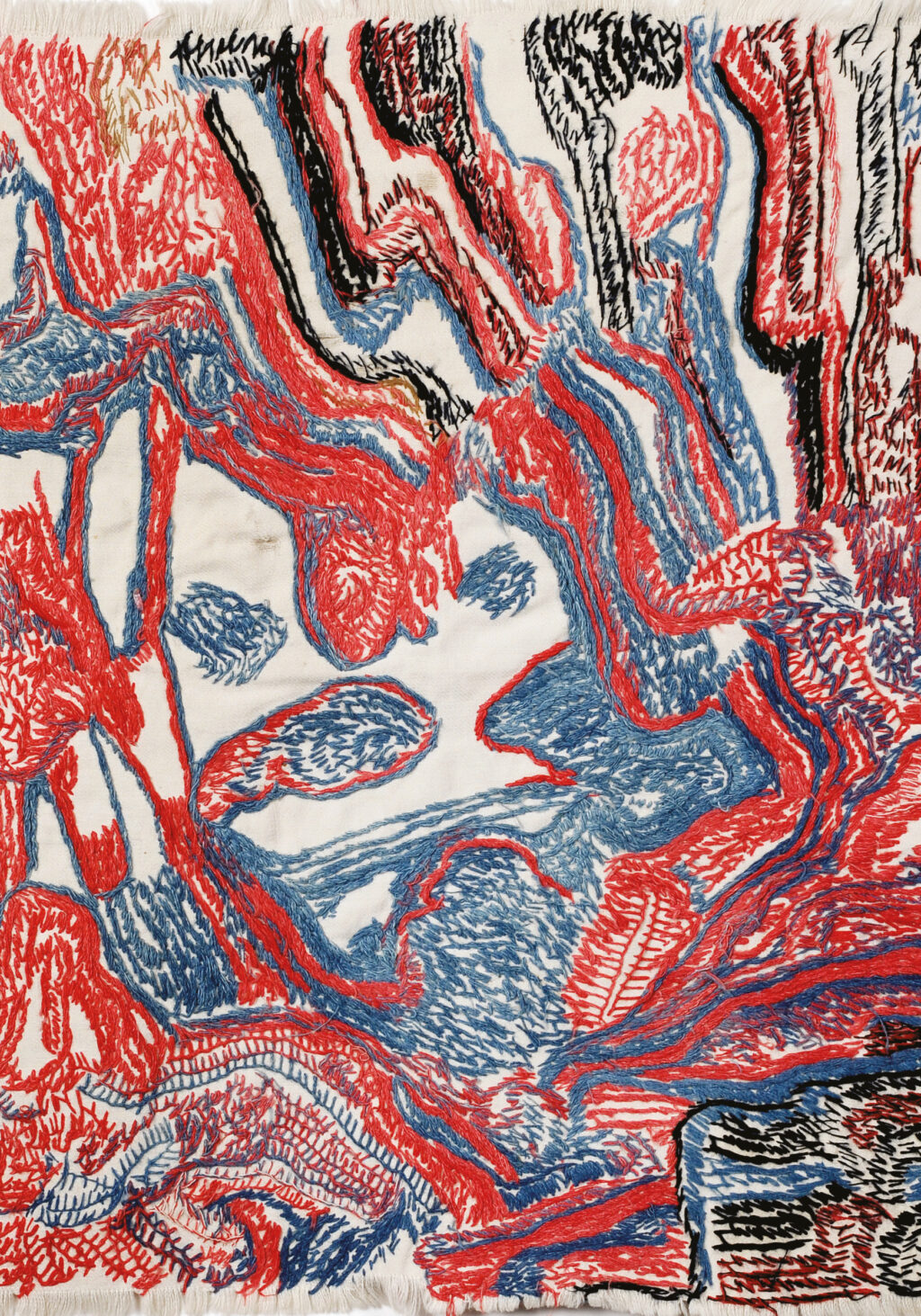

’She often tears bedsheets or linens into pieces to obtain fabric for her inventions.’

This quote from Maria Rudbeck’s (1866-1955) medical records demonstrates her desperate need to express herself. The ability – or the permission – to create art could not be taken for granted. Getting access to embroidery materials was difficult, but that was nothing compared to books and booklets. Materials were frequently unavailable.

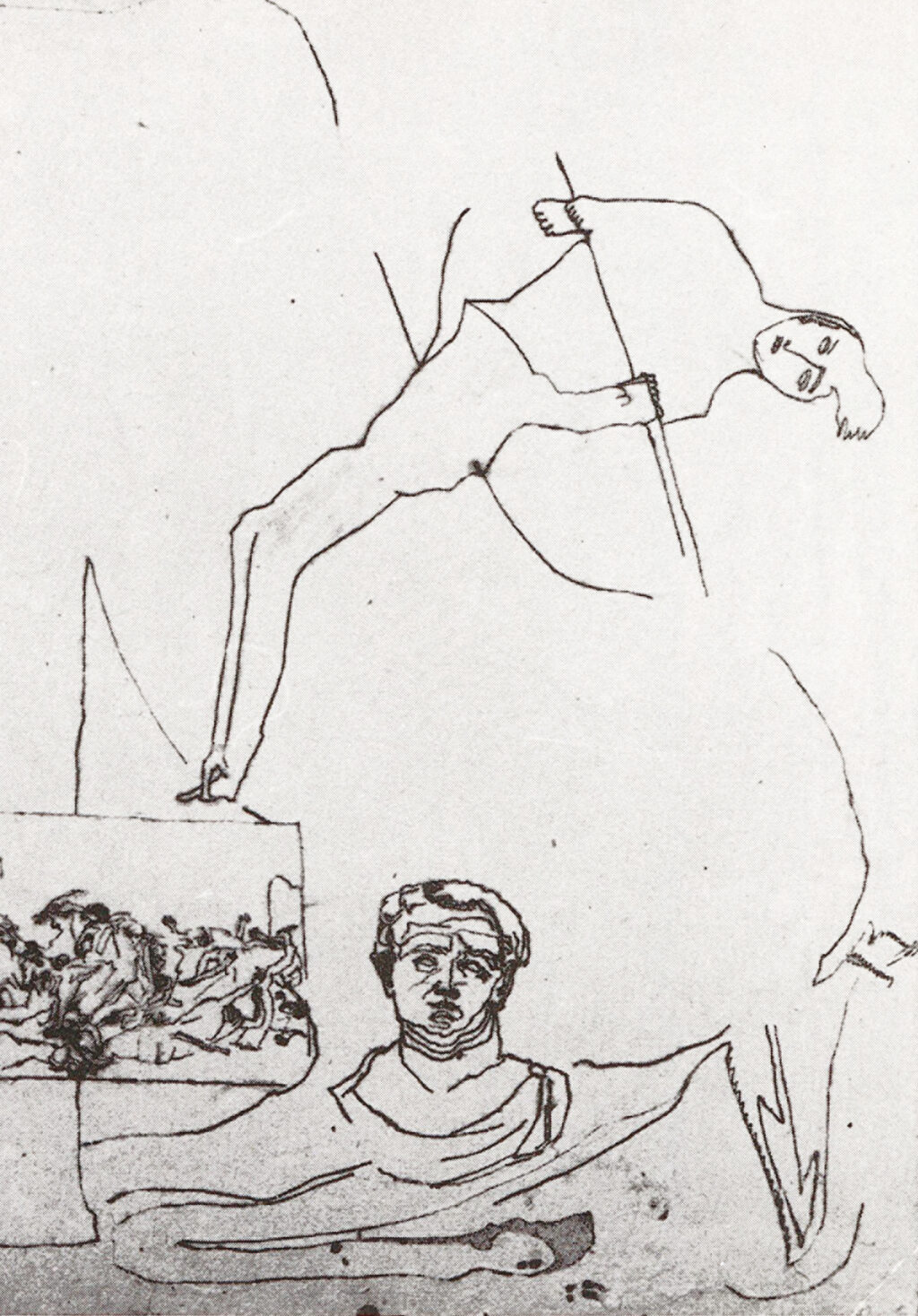

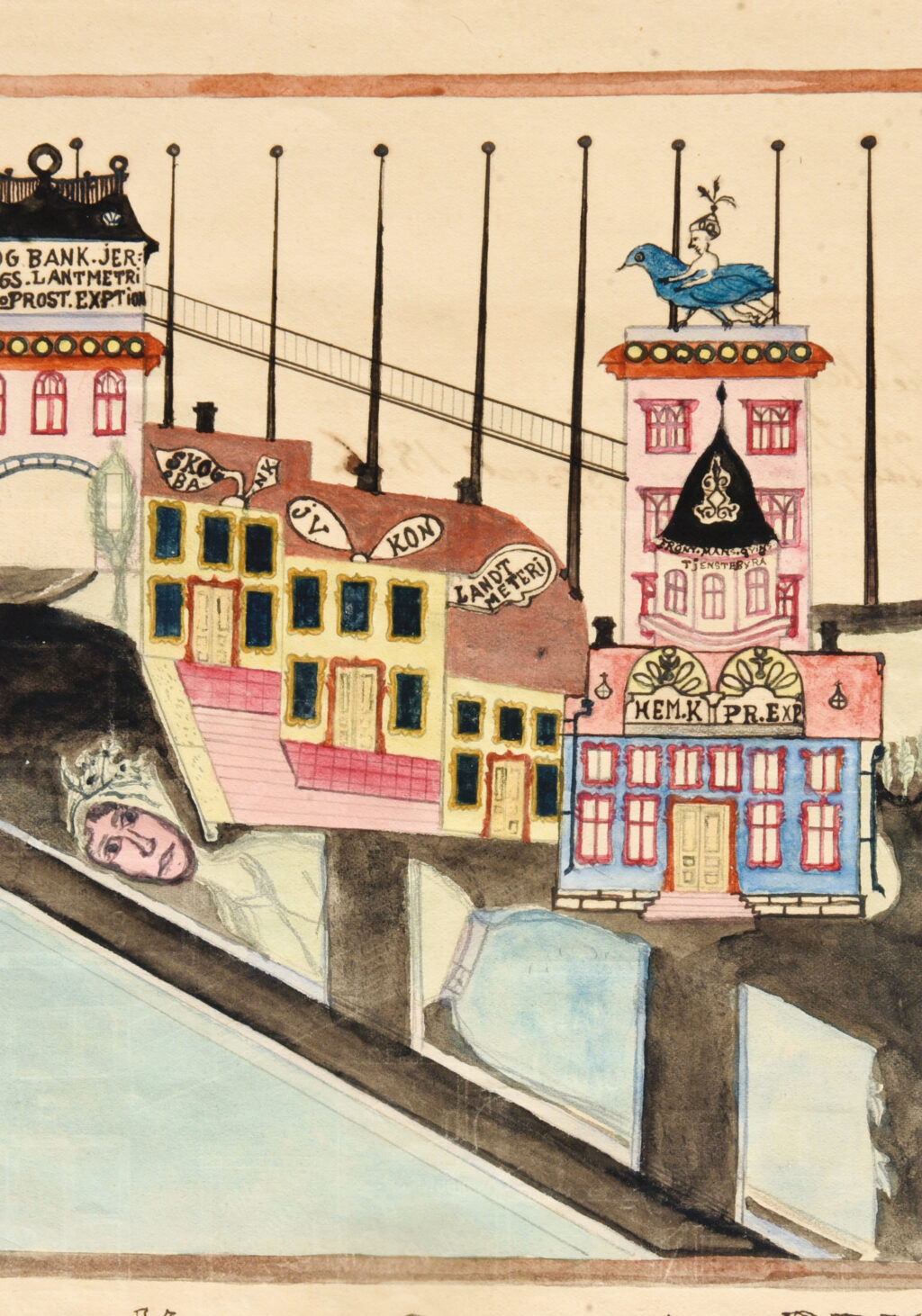

The oldest book in Region Skåne’s medical history collections to have been created by an artist is Peter Eklund Persson’s Sketchbook, 1901-1904. The fortunate fact that it has been preserved at all probably has something to do with its format and detailed, thorough content. The book was made by Eklund as ‘Emperor Ollokrantz’ and portrays his kingdom of Jämtland – its buildings and their construction drawings, vivid details, as well as portraits and accounts of his subjects.

Someone must have given Rudolf Persson (1882-1939) a German Musterzeichenheft, from which you are really meant to copy the patterns printed on each page. He ignored the copying, and filled the book with fantasies regarding the ‘Montenegrin-Turkish War’, most likely inspired by the Balkan War of 1912-1913. The Montenegrins, who were his favourites, won several battles, sometimes with the help of ‘Eskimos in kayaks’ and heroes of the ancient world. Persson seems to have been a kindred spirit to the considerably more famous American Henry Darger and his ever-battling Vivian Girls.

Despite the amazing art, it is hard to dismiss all the tragic fates. During Maria Rudbeck’s 53 years in Sankt Lars, a grand total of three (!) visits were recorded. According to the author Kerstin Strandberg, Rudbeck’s guardian forgot to apply for the annual pension of 200 SEK that all patients were entitled to. That money would have come in useful. ‘[Rudbeck] has read all the books in the hospital library and would dearly like to buy a book once in a while.’ (Dagens Nyheter, 14 January 1996)

Rudbeck was a teacher who had been subjected to attempted rape while working as a governess for a Swedish family in Austria. When she came back to Sweden, she worked as the headmistress of a school until she developed depression. She was hospitalised in 1902. Her condition worsened over the years, she was considered unruly and an escape risk.

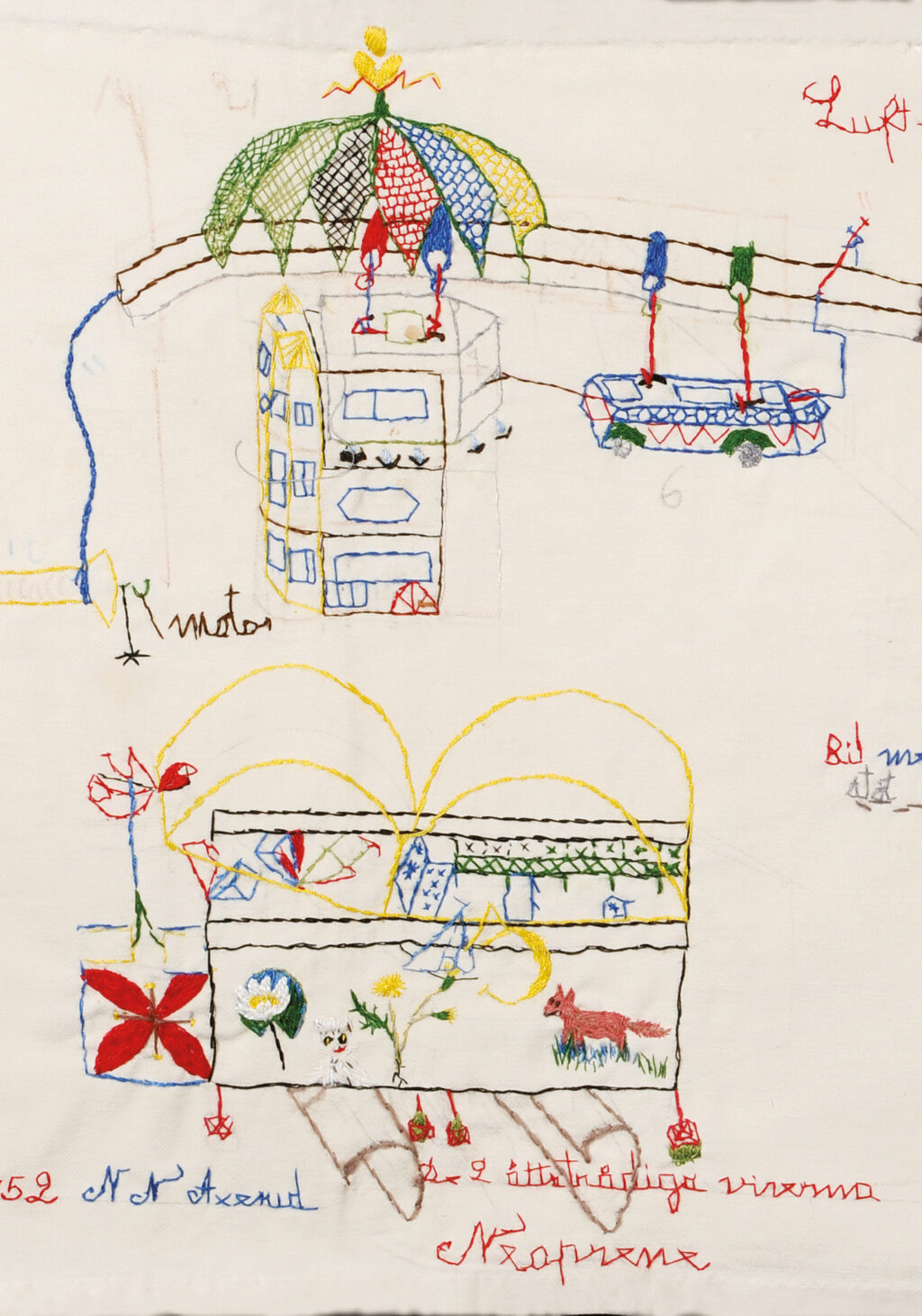

Rudbeck has become known for her embroideries containing commentaries on current affairs, and drawings of peculiar aircrafts and vehicles with names like Voalj, Vadesendrum, Airodrome and Erostat. She invented a device that would prevent her nightmare of ending up in suspended animation. It combined a knife and a grinder and was called the Mos-atom-in-Deum-döden-dö (‘Mash-atom-in-Deum-death-die’).

She collected her inventions and her detailed drawings and descriptions in four Invention books in the years around 1950. Page after page, they chart a truly fantastical exploration into the unknown.

In some places, Rudbeck as a person shines through. Bok 2 smårutig (‘Book 2 small-checked’), from 1949, contains a picture of Snow White, who was taken to the woods to be killed by the hunter. As we know, she got away. Rudbeck was perhaps thinking of how her own, unknown parents had left her with foster parents, who, in turn, had abandoned her in Sankt Lars to disappear and die.

It would be questionable to refer to Rudbeck as an uneducated artist. At the time of her admission, she had been given a middle-class education. It would not be far-fetched to compare her Invention Books to a similar project many years later, Sten Eklund’s Kullahusets hemlighet, from 1971. The observations made by author Lotta Lotass can be applied to Rudbeck as well. The fictious explorer ‘Paléen realises that he exists in a borderland between speech and silence. He becomes inexorably confined, trapped in the experience that he is, in vain, trying to convey to others as well as clarify and explain to himself’ (Kullahusets hemlighet, 2016).

The language, written in Rudbeck’s beautiful hand, in combination with the drawings, create a mental map – of the silence that surrounded her, if you like. I would like to put the following words by Sten Eklund’s ‘Paléen’ in her mouth: ‘In short, I imagined that anything could be brought to life through clear and concise language. I know better now.’ (Kullahusets hemlighet).

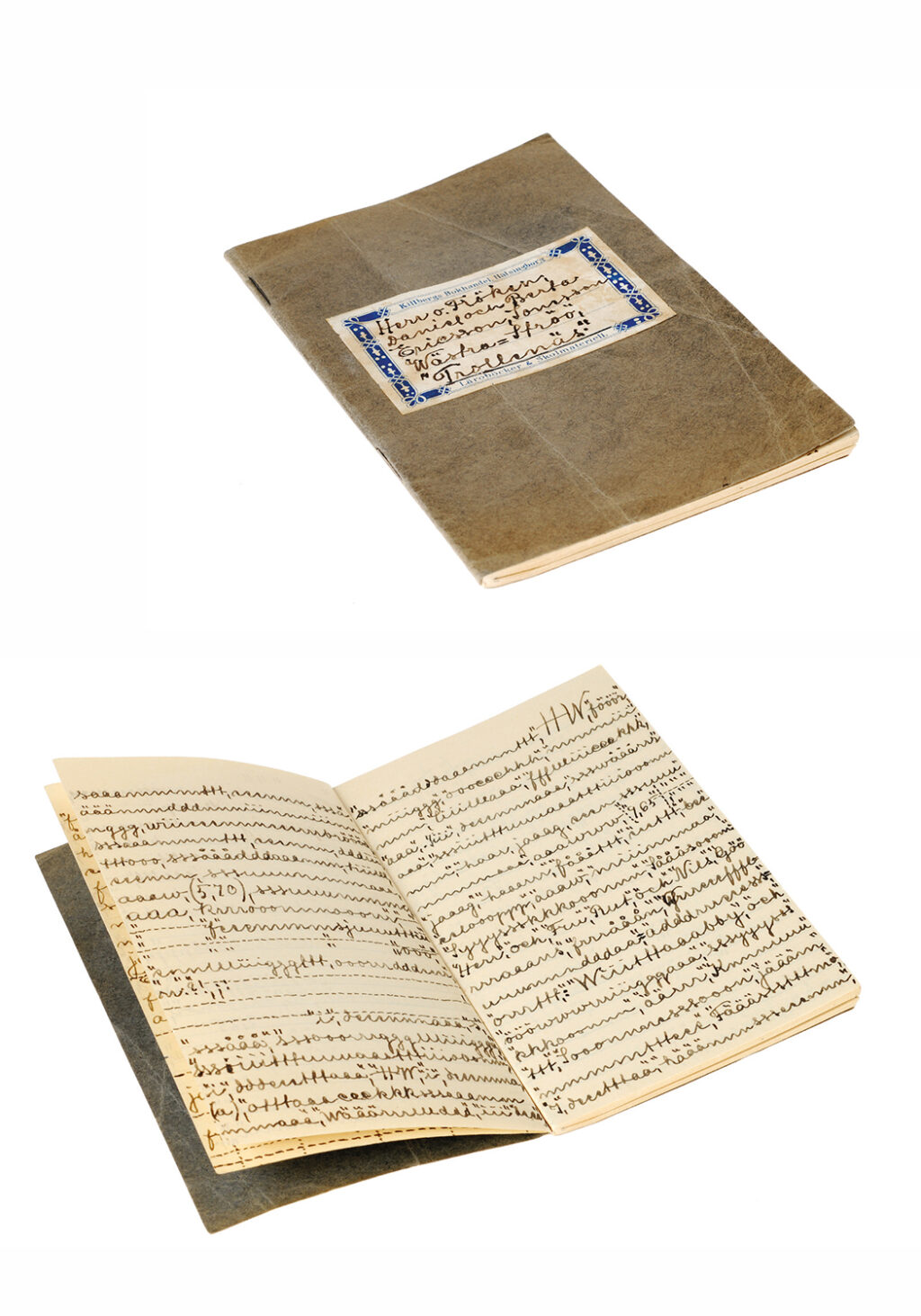

The same applies to a worn, well-thumbed notebook. The label reveals, in a neat hand, its owners’ names:

Mr and Miss

Daniel o Berta

Ericsson Sonesson

Wästra Ströö

Trollenäs

At first, I thought that Sone Daniel Sonesson (1899–1976) and Berta Ericsson (1906–2001) had written the booklet together. They were childhood friends from Västra Ströö, but they went their separate ways. The booklet is obviously Sonesson’s. Initially, he was admitted to an institution in Helsingborg in 1932, and he died in a nursing home in Trelleborg 44 years later. The little booklet was created during his time in Sankt Lars between 1943-1949.

Sonesson’s handwriting is narrow. Every line, every word, every syllable and letter stretched out and extended until the text almost looks like asemic writing. Some words are recurring, like the placename Västra Ströö and his childhood friend Berta Ericsson. Varied, twisted, drawn out. In some places, his strong emotions break up the text. ‘In this Fiendish World’ or the longing for ‘my little girl’, that is, Ericsson.

But his energetic writing style dissolves reality and thoughts into a grammatical and orthographic flicker. It refers to what he has left behind, interchangeably distant and close. I can read the flow of his writing much better with the words of the Austrian poet, Ernst Herbeck (1920-1991) in mind. Like Sonesson, he spent time in a mental institution.

Homesickness

I do not just long for home,

it is more than that. Homesickness

is torture without parallel.

One cannot endure

standing outside. I

want to be allowed home.

(Ernst Herbeck)

Sonesson’s booklet measures up to Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd’s scribbling from the 1950s or Åke Hodell’s painful book, CA36715 (J), from 1966. The language dissolves into tentative coils and tendrils, clarifying the incomprehensible through its shapelessness. If you like – a language of necessity beyond ordinary language.

Sonesson’s booklet is carried by a dualism he did not quite know what to do with. His medical records from the time of admission in 1932 state: ‘Considers himself half man and half woman, and speaks, as a man, with a deep voice and, as a woman, with a squeaky voice’. He also mentions his childhood friend, Ericsson. In the booklet, her role alternates between being an object of yearning and a presence in his inner self. These roles do not necessarily contradict each other. He is two – man and woman – but he cannot succeed in uniting this double person through his writing.

Finally, Sonesson dreams of a funeral – and vindication. ‘Certainly, there was such a good man and woman called Dalle Berta or Daniel Berta Sonesson Ericsson in this world. In this soil I would someday like to wed my Soul Mate.’ To Sonesson, this language seems to have been a way of escaping the denial shown by the hospital and the authorities regarding his identification with both genders.

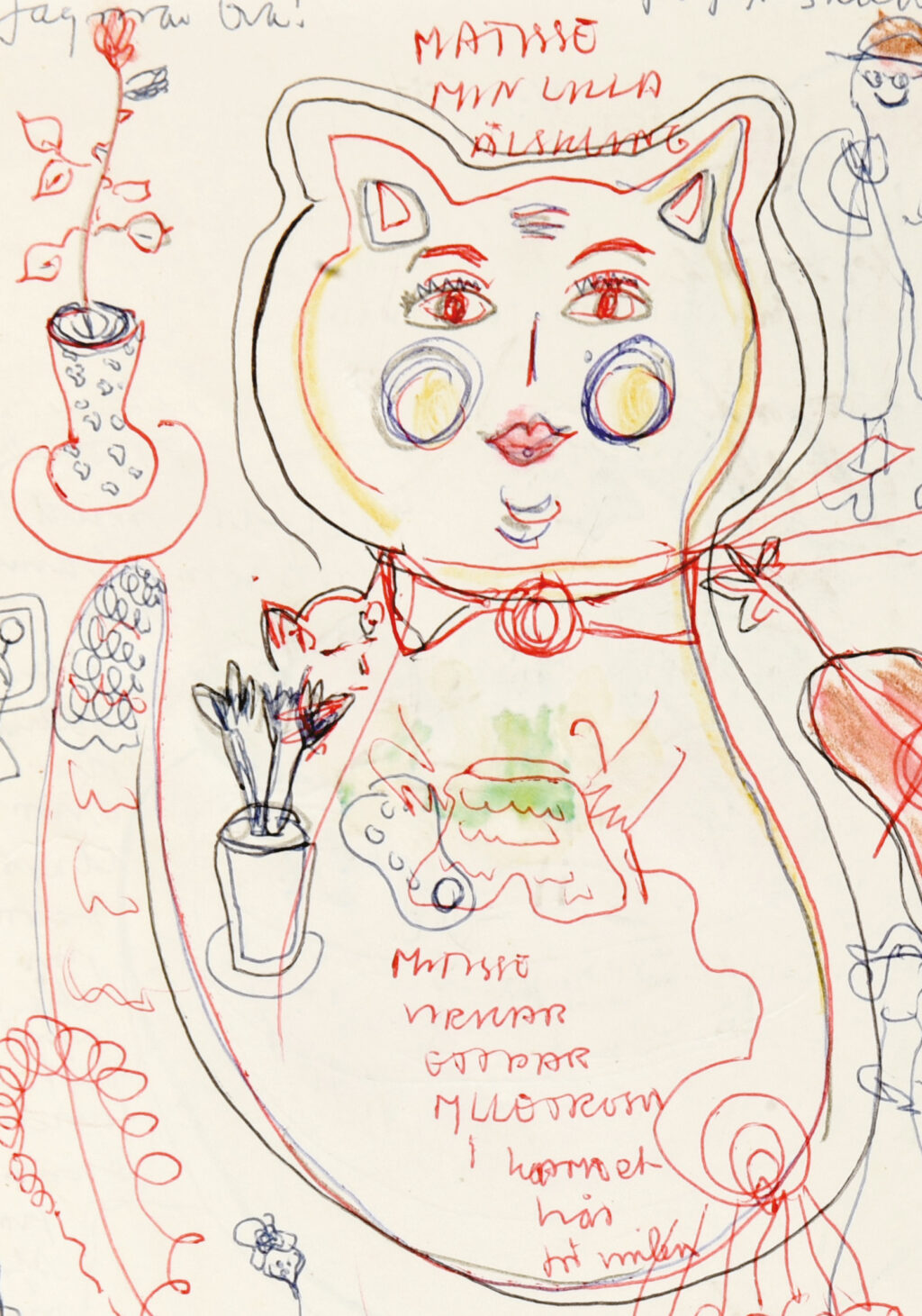

Britta Sjögren (1930–2001) was a textiles teacher – you can tell by the books she has read and appropriated. Yarn, colour and pens are combined. In a copy of Astrid Lindgren’s anthology, I diktens träd, from 1994, she has enthusiastically covered poems and verses with colourful images. And in Marie Cardinal’s Orden som befriar (‘The words to say it’), from 1978, she has imposed herself on the text, placing a seated female figure in the middle of a passage about children. It is a representation of herself, with an added comment that she is old already, 64 going on 65. This appropriation of books was a way for her to penetrate what she read and take over, take it in, a phenomenon with many parallels within the field of artists’ books. Sjögren’s, overflowing with emotion, is one of the most intense.

This intensity is caused by the density of characters, where language falls short, something that certainly constitutes a link between the artists I have mentioned.